Experimental Women In Flux

Selective Reading in the Silverman Reference Library

In 2009 The Museum of Modern Art acquired The

Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection—a private collection

devoted to the Fluxus art movement. Fluxus, with roots in experimental

music, emerged in the United States and Europe in the early 1960s. With

an emphasis on performance and play, Fluxus artists aimed to bring art

and life together, collapsing the traditional divisions between mediums

and undermining the authority of the artist through collaboration and

audience participation. Along with artworks and the archives of The

Gilbert and Lila Silverman Foundation, the acquisition includes the

Silverman Reference Library, a collection of more than 1,500 artists’

books, exhibition catalogues, periodicals, and scholarly works, all of

which are now held in the Museum’s library. These materials document the

activities of artists integral to Fluxus and others on the periphery of

the movement—precursors, contemporaries, and artists of succeeding

generations whose artistic practices overlapped with Fluxus in group

exhibitions, critical writing, and experimental magazines.

In this collection, which documents a

range of avant-garde activities over several decades, networks of

artists materialize in print. One conspicuous network is composed of

women—the many female artists who helped shape Fluxus aesthetics and the

numerous others associated with the group. Fluxus developed in the

decade leading up to the women’s movement, and the prevalence of female

participants in its diverse activities was unprecedented. The women

featured in this exhibition created various forms of intermedia

art—falling somewhere between visual art, poetry, performance, and sound

art; they acted as interpreters of works by others and hosted seminal

concert series that enabled avant-garde movements to flourish. In doing

so they contributed to the expanding parameters of artistic expression

that characterized their era while redefining “women’s work” for the

female artist.

The exhibition is organized by Sheelagh Bevan with David Senior, The Museum of Modern Art Library.

Action & Performance in Print

Fluxus

performance—concerned mainly with the interaction between human bodies

and the objects and actions of everyday life—debuted in 1962 in a series

of concerts across Europe organized by artist George Maciunas. The

history of performance by Fluxus women as documented in the Silverman

Reference Library is necessarily incomplete, giving only a partial view

of the live, ephemeral, and durational work, which by its nature

frustrates the limitations of print. The Library also touches on the

roots of performance art and the contemporaneous existence of Nouveau

Réalisme and Happenings—whose female participants’ contributions were

largely unacknowledged, if not anonymous.

|

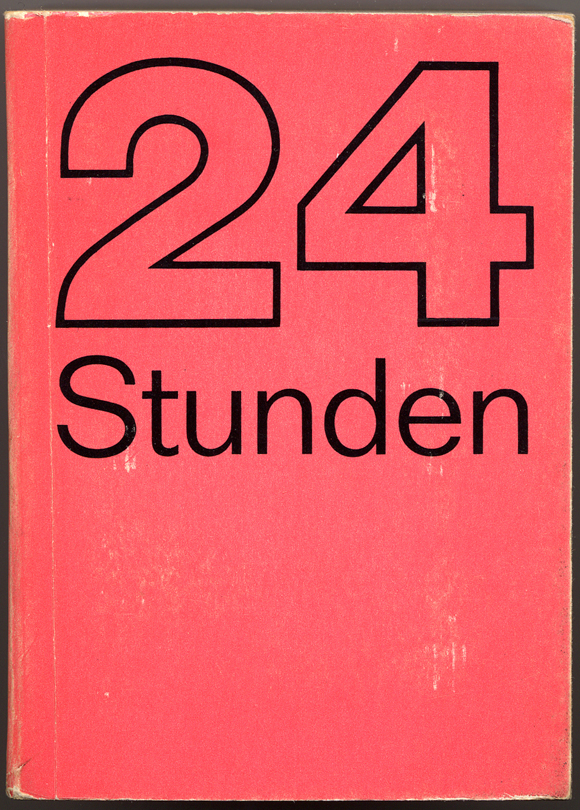

[top of page] Ute Klophaus. Charlotte Moorman at the Galerie Parnass, Wuppertal, June 5, 1965. In 24 Stunden (Hansen & Hansen, 1965).

Moorman was the lone female participant in the twenty-four-hour Happening 24 Stunden

(24 hours) in Wuppertal. The event’s organizers added Klophaus to the

list of participants in the catalogue, blurring the line between

documentation and participation.

|

Klein’s painting took on a performative element when he used nude women as “living paintbrushes,” making his Anthropométrie (Anthropometry) paintings in front of a seated audience.

Niki de St. Phalle, 1961. In Nouveau Réalisme, 1960/1970 (Rotonda della Besana, Comune di Milano, 1970).

St. Phalle initiated her own form of action painting in her Tir

(Shooting) series of paintings. To make the works the artist and,

later, her audience shot rifles at canvases prepared with bags of paint.

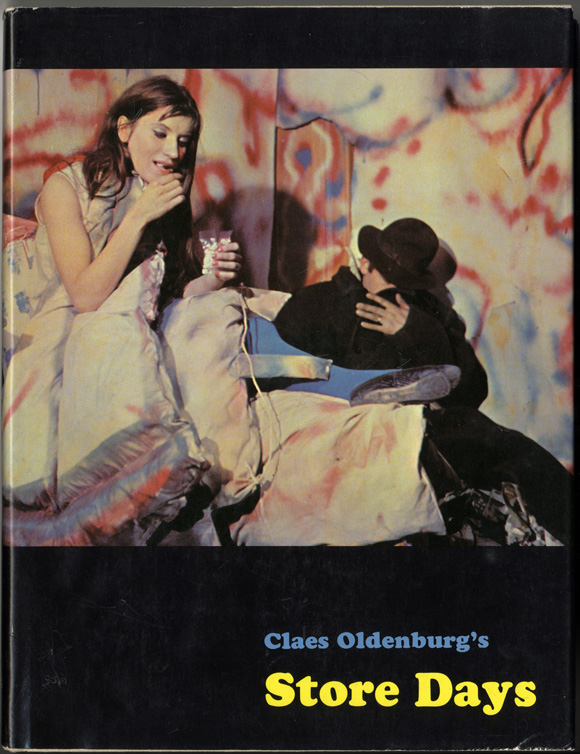

Patty Mucha. In Store Days: Documents from The Store, 1961, and Ray Gun Theater, 1962, ed. Claes Oldenburg and Emmett Williams (Something Else Press, 1967). |

|

Mucha, shown here performing with Claes Oldenburg, also collaborated in sewing costumes and constructing objects and sets for Oldenburg’s Happenings and installations.

Charlotte Moorman. In 24 Stunden (Hansen & Hansen, 1965).

Moorman forged a unique career in the

gray area between composer and performer created by the opportunities

for individual interpretation in Fluxus compositions. She founded the

Annual Avant Garde Festival (1963–80) in New York, bringing together

Fluxus artists with experimental poets, artists, dancers, and musicians

of all kinds.

Shigeko Kubota, Yoko Ono, Mieko Shiomi,

and Alison Knowles all collaborated on performance-based works that

often took common activities as their material. These Fluxus artists

believed that the acts of preparing food, marrying, smiling, playing

games, or rustling a newspaper were forms of “social music,” making life

itself a ready-made work of art. Solo performances by women were not

always playful, however, and some took on more intimate or

confrontational tones. Women involved in Fluxus have primarily

characterized their experience in these events as liberating, as giving

them a sense of artistic independence. However, the images of women in

these early catalogues and magazines—all of which were edited by

men—tell multiple, contradictory stories of artistic agency and

vulnerability that feminists and art historians continue to debate.

|

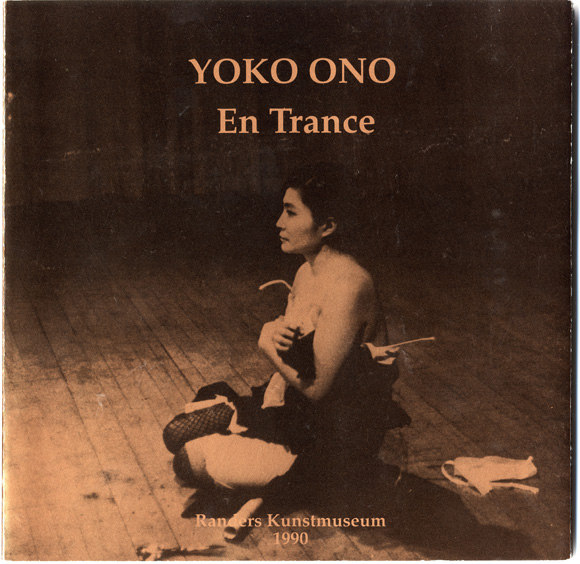

[left] Yoko Ono. Cut Piece. 1965. In En Trance (Randers Kunstmuseum, 1990).

Ono, like Shigeko Kubota and Mieko

Shiomi, was part of a community of Japanese experimental artists and

musicians who found artistic independence in New York. In Cut Piece

Ono signaled what was to become a life-long exploration of audience

participation. In a gesture of interactive sacrifice she invited members

of the public to cut her clothing with scissors.

[above] Shigeko Kubota. Vagina Painting. 1965. In VTRE, no. 7 (1966). Photographs by George Maciunas

|

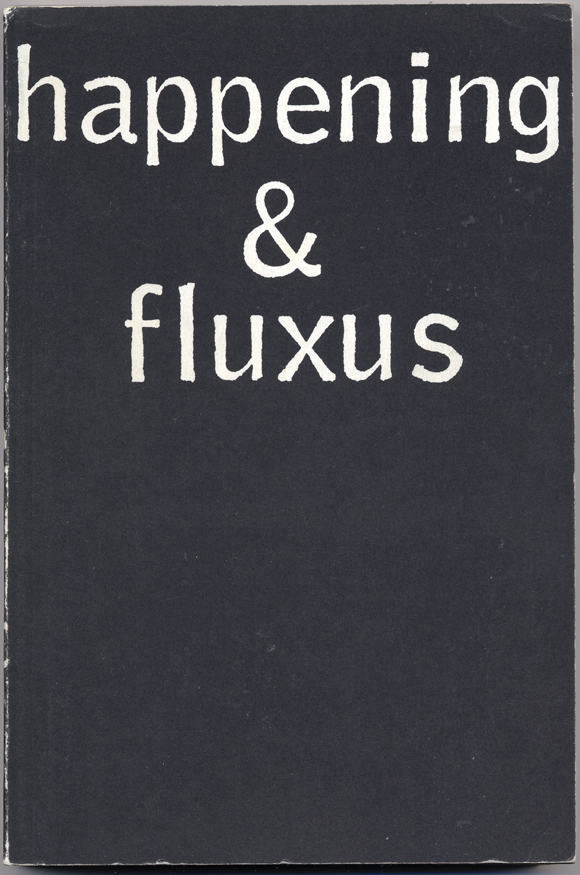

Lette Eisenhauer in Lick Piece, by Benjamin Patterson. 1964. In Happening & Fluxus: Materialen, ed. Hanns Sohm (Koelnischer Kunstverein, 1970). Photograph by P. Moore

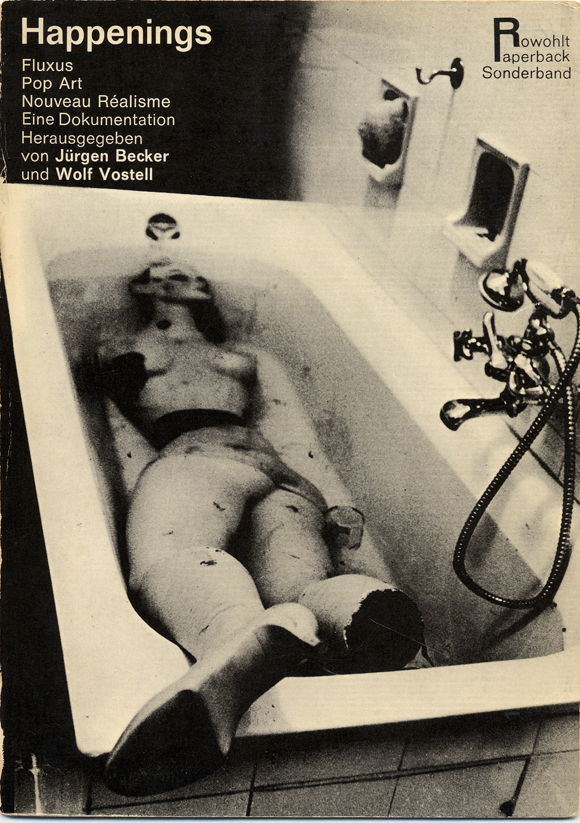

Alison Knowles in Danger Music, by Dick Higgins. 1961. In Happenings, Fluxus, Pop Art, Nouveau Réalisme: eine Dokumentation, ed. Jürgen Becker and Wolf Vostell (Rowohlt, 1965).

Alison Knowles remained closely involved with Fluxus

throughout the 1960s and ‘70s. She is shown here shaving the head of

fellow Fluxus artist Dick Higgins, as she performs the final part of his

five-word score: "Hat. Rags. Paper. Heave. Shave."

“Lady Mystica” in Composition for Lines and Composition for Alarm Clocks, by Bob Lens. 1964. In Fluxus in Holland: the Sixties, ed. Harry Ruhé (Galerie A/artKitchen Gallery, 2009).

Monique Smit in Sun in Your Head, by Wolf Vostell. 1964. Photo by Igno Cuypers. In Fluxus in Holland: the Sixties, ed. Harry Ruhé (Galerie A/artKitchen Gallery, 2009).

Billie Hutching and George Maciunas. Flux Wedding (Money for Food Press, 1978). Photographs by Hollis Melton

Both the social and subversive

elements of Fluxus informed the artistic presentation of the marriage of

poet Billie Hutching and Fluxus organizer George Maciunas. The bride

and groom each wore women’s gowns, then exchanged them at the altar. The

photographs, marriage certificate, and guest registry were later

published as a performance score.

|

|

Textual Scores and Instructions

For artists associated with Fluxus, the concepts, from music, of the score and the arrangement

provided the structural basis of both performance and the methods of

recording it. The Silverman Reference Library contains numerous scores

and instructions for performances that expand on Fluxus artist George

Brecht’s notion that music “isn’t just what you hear . . . but

everything that happens.” These texts by women combine thought,

perception, and imagination as equal parts in a multisensory music that

relies on the reader for realization.

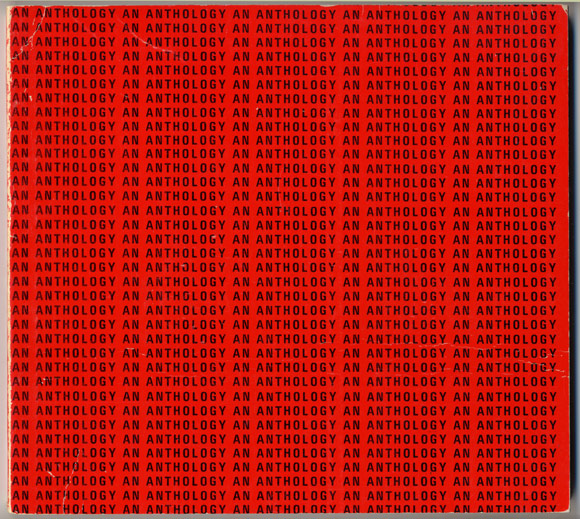

Simone Forti. [Dance Constructions]. In An Anthology, 2nd ed., ed. La Monte Young (H. Friedrich, 1970).

In the first publication to compile

scores by members of Fluxus, the dancer Forti contributed instructions

that could be performed by nondancers, realizing one of the group’s main

tenets: anyone can create art.

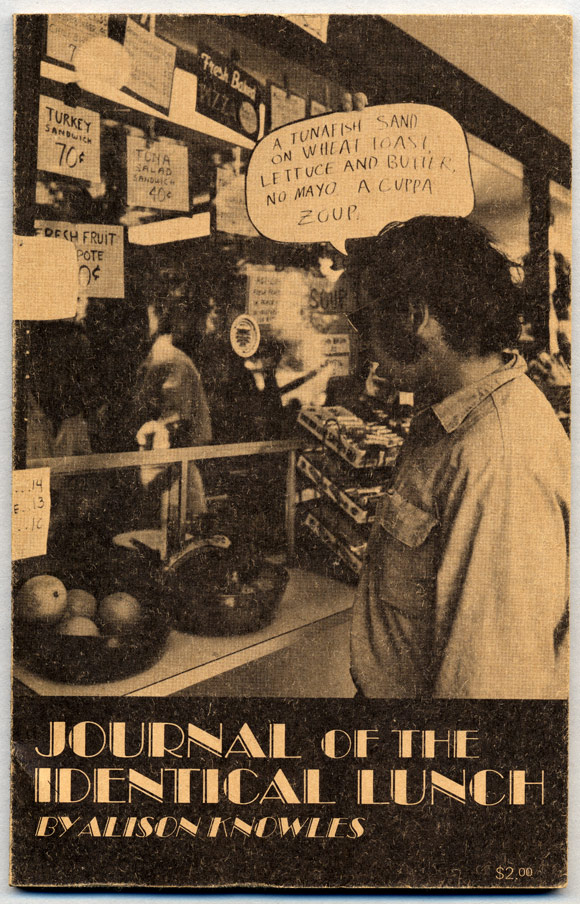

[below] Alison Knowles. Journal of the Identical Lunch (Nova Broadcast Press, 1971).

This book documents Knowles’s daily

lunch of a tuna sandwich at the Riss Diner in New York, while devoting

more space to the subsequent “arrangements” performed by friends and

fellow artists. She later expanded the work in a series of

screen-prints, now on view in the museum’s Contemporary galleries, and

will perform the work at MoMA in 2011.

|

Philip Corner. The Identical Lunch: Performances of a Score by Alison Knowles (Nova Broadcast Press, 1973).

Fluxus artist Philip Corner

convinced Knowles to create a score from her daily meal, and later

published his own book-length arrangement of the work.

Poesie et Cetera Americaine: Biennale Internationale des Jeunes Artistes (Musée d’art moderne de la ville de Paris, 1963).

Alison Knowles’s Shuffling Piece (for audience) and Simone Forti’s Instructions pour une danse

were two of seven compositions performed simultaneously at the 1963

biennial for young artists in Paris. In the list of participants in the

back of the program, les spectateurs (the spectators) were included along with the roster of artists.

|

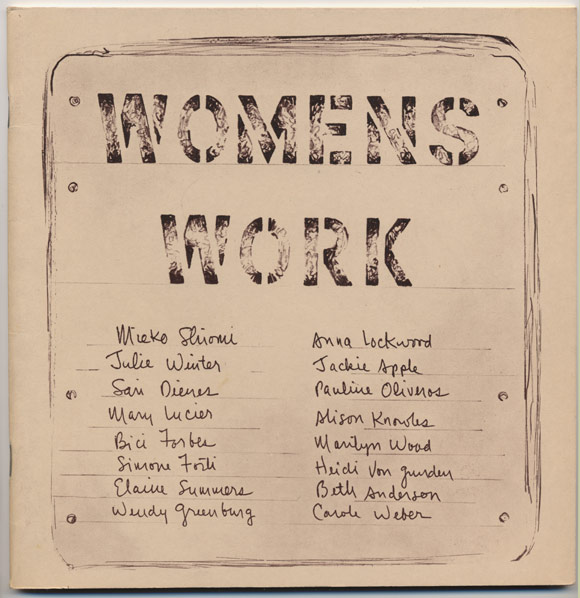

Anna Lockwood et al. Womens Work (self-published, 1975).

This collection, edited by Alison

Knowles and composer Annea Lockwood, was the first to bring together

textual scores exclusively by women.

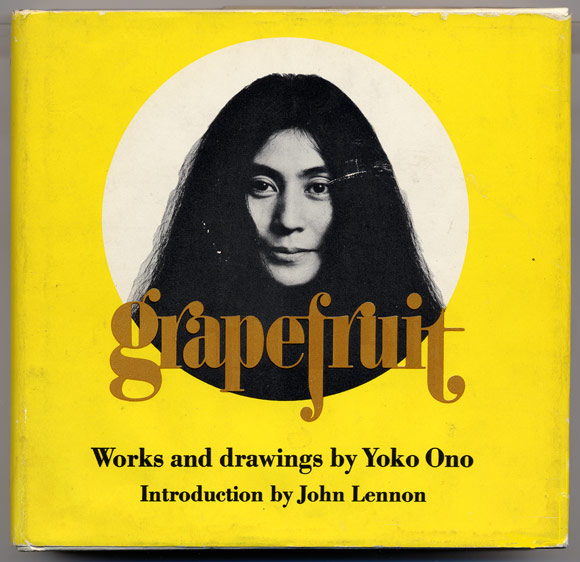

Yoko Ono. [Scores from Grapefruit]. In Yoko Ono: To See the Skies, ed. Jon Hendricks (Mazzotta, 1990).

Ono, an early advocate of the genre, has

created, performed, and published event scores throughout her career.

Her early collection Grapefruit (1964) was the first ever presentation of textual scores by a single artist in book form.

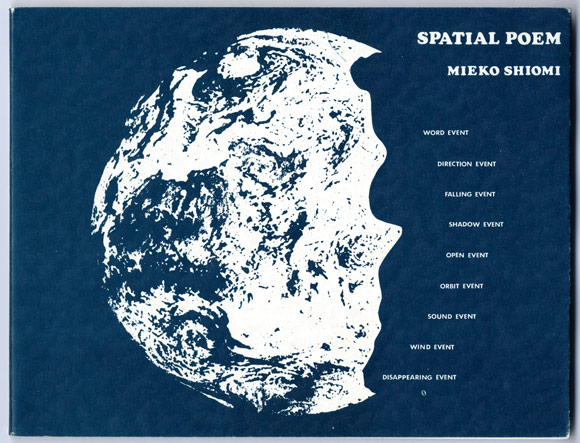

Mieko Shiomi. Spatial Poem (M. Shiomi, 1976).

Mieko Shiomi. Invitation to Spatial Poem no. 4. 1975

Mieko Shiomi. Invitation to Spatial Poem no. 4. 1975

Shiomi demonstrated the collaborative aspect of Fluxus and the group’s influence on developments in mail art in Spatial Poem

(1965–75), a “global event” in which she enlisted artists through the

mail to document their participation in her intimate action poems.

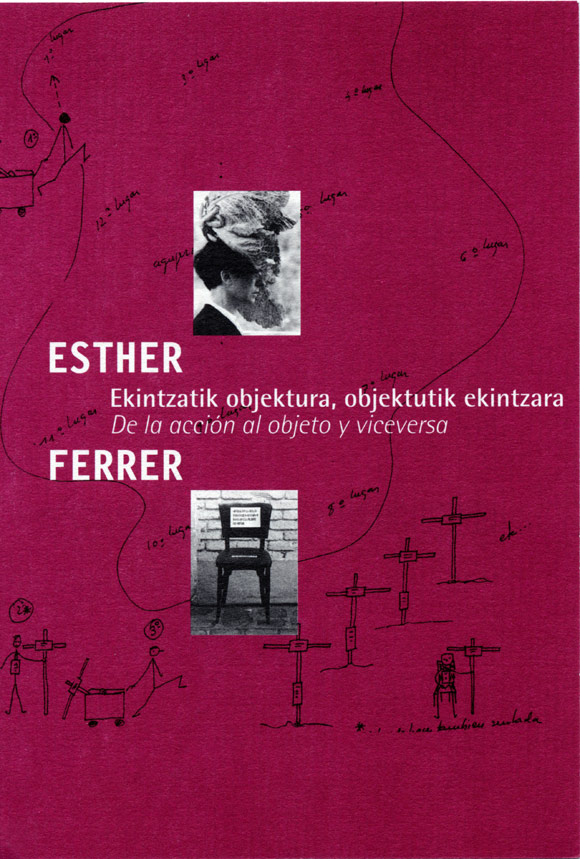

Esther Ferrer. Le Fil du Temps. In Esther Ferrer: Ekintzatik Objektura, Objektutik Ekintzara (Gipuzkoako Foru Aldundia, 1997).

One person sits on a chair. From the ceiling, a

very fine thread starts falling. The person remains seated until the

thread covers him/her completely.

Ferrer incorporates drawings and

related installations into her texts. She often emphasizes the absurdity

of life by including suicide as one possible outcome of her actions. An

early member of the experimental music and performance group Zaj, based

in Spain, Ferrer today remains committed to exploring the concept of

performance in multiple mediums.

Katalin Ladik. Novi Sad (Projects). Wow, Special Zagreb Number, ed. Bosch + Bosch (1975).

|

|

Ladik’s scores elicit reflections on and

interventions into the physical environment of Novi Sad, Serbia. Ladik

was the only female member of Bosch + Bosch, an art collective based in

Subotica, Serbia, whose diverse activities touched on performance,

Conceptual art, land art, sound art, and visual poetry.

Visual Music

Graphic notation—the use of symbols,

images, and texts to transcribe music—emerged in the middle of the

twentieth century, as composers began to investigate the borders between

musical notation and visual art. For Fluxus artists, many of whom had

been classically trained in the field, music served both as a mode of

composition and a medium of sound and visual art. Producing works that

employ combinations of drawing, calligraphy, texts, and collage, women

created their own systems of notation. Other women artists in dialogue

with the group worked closely with composers to interpret or enhance

music through the traditional mediums of painting, sculpture, and

photography. Male composers inserted the female body into new types of

symphonic scores as a compositional element, but this objectification

was countered by the prolific production of women—a small selection of

which appears here.

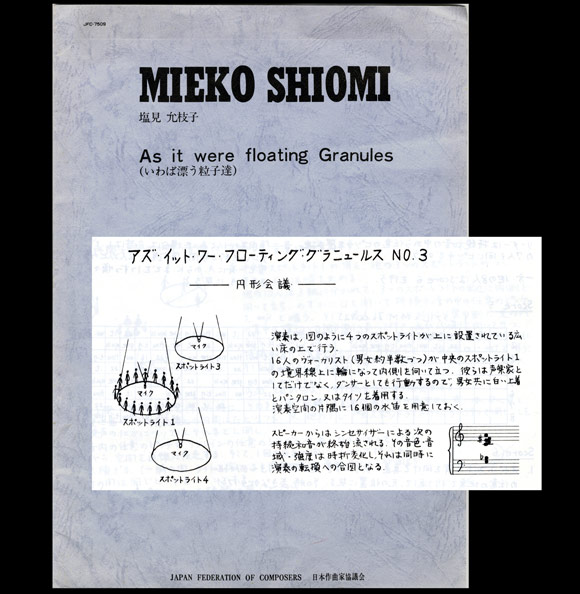

Mieko Shiomi. As It Were Floating Granules (Japan Federation of Composers, 1976).

Shiomi was a cofounder of the Japanese

experimental music collective Group Ongaku, with which she collaborated

before and after her Fluxus years in New York. This six-part work—a

chance composition for vocal groups and instrumentalists—employs a range

of graphic notational systems and texts in English and Japanese.

Mieko Shiomi. Lyric Suite (Self-published, c. 1973).

This is one of six collages in Shiomi’s visual music portfolio Lyric Suite.

More than any other female member of Fluxus, Shiomi, in her work as

composer, visual artist, and performer, repeatedly returns to music as a

ground for experimentation.

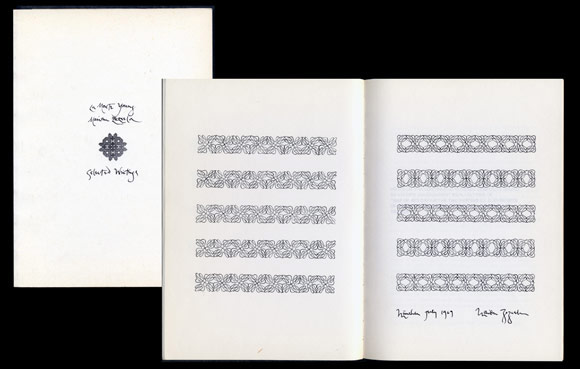

Marian Zazeela. Lines. In Selected Writings, Copyright © La Monte Young and Marian Zazeela 1969 (Heiner Friedrich, 1969, Munich)

Zazeela’s use of systems of abstract calligraphy in

her work in the early 1960s is evidenced by the posters and cover art

she designed for Young, a composer. As their close collaboration

progressed, Zazeela inflected these inscriptions with color, expanding

them into innovative light installations that formed an integral part of

Young’s musical performances.

Dora Maurer. Time Pieces. In Source, no. 11 (1972).

Maurer, a filmmaker and visual artist,

used photography and a language of time to depict the underlying

structure of music. This work appeared as part of an exhibition-in-print

on contemporary approaches to music, published in the avant-garde music

magazine Source.

Alison Knowles. Blue Ram. 1967. In Notations, by John Cage (Something Else Press, 1969).

Knowles helped to design and edit Cage’s

compilation of new musical scores. Her own contribution to the

collection is a composition involving four performers, sound-making

objects, and six illustrated cards.

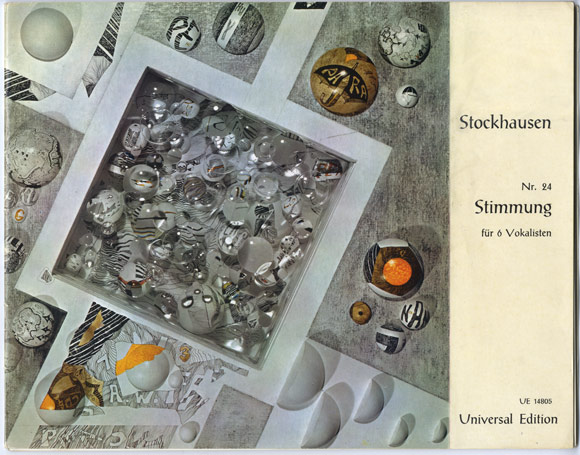

Mary Bauermeister. Peng-cil. 1966. In Stimmung, für 6 Vokalisten, nr. 24, by Karlheinz Stockhausen (Universal Edition, 1969). Library copy

Bauermeister’s Cologne atelier was a

center of experimental music for the European and American avant-garde,

some of whom became involved with Fluxus. Bauermeister’s approach to

painting inspired Karlheinz Stockhausen, the electronic-music composer,

and their work was exhibited together in multimedia exhibitions. As part

of the score for Stockhausen’s musical play Originale (1961), Bauermeister painted onstage—a feat she later repeated alongside Fluxus artists at Charlotte Moorman’s Annual Avant Garde Festival.

Nam June Paik. Symphony no. 5. 1965. In Happenings, Fluxus, Pop Art, Nouveau Réalisme: eine Dokumentation, ed. Jürgen Becker and Wolf Vostell (Rowohlt, 1965).

Mieko Shiomi. Selections from Fluxus Suite: A Musical Dictionary of 80 People around Fluxus

(? Records, 2002).

(? Records, 2002).

Shiomi composed musical portraits of eighty figures associated with Fluxus. These selections represent Jean Brown, Esther Ferrer, Alice Hutchins, Alison Knowles, Shigeko Kubota, Barbara Moore, Charlotte Moorman, Pauline Oliveros, Yoko Ono, Takako Saito, Carolee Schneemann, Mieko Shiomi, and Marian Zazeela.

Forms of Writing

For women artists associated with

Fluxus, language was a site of aesthetic inquiry and play. The textual

elements of many Fluxus artworks led to their inclusion in literary

collections and underground magazines at a time when American art

magazines did not devote much space to the group. In the little

magazines of the 1960s and 1970s, work by Fluxus writers is presented

beside work by the Beats, new poets of San Francisco, New York, and

England, and visual poets from around the world, some of whom were also

exploring the use of sound, images, and new technology in language arts.

|

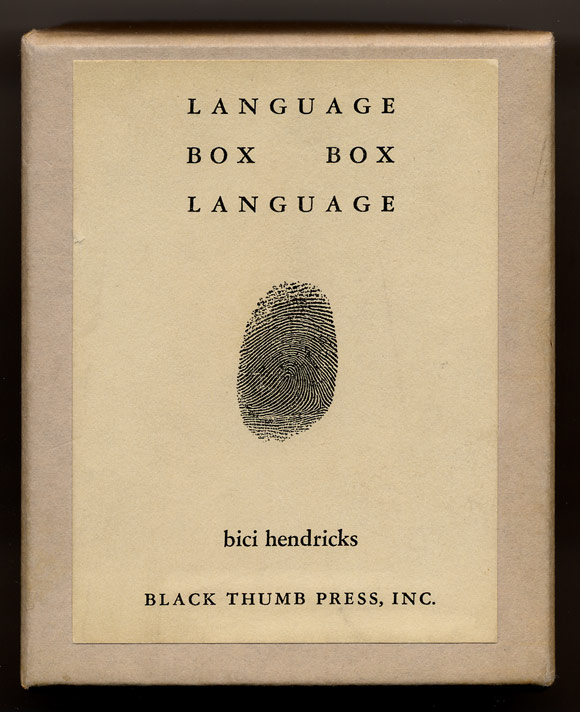

Bici Hendricks. Language Box, Box Language (Black Thumb Press, 1966).

Nye Ffarrabas, known then as Bici

Hendricks, has described her book as a game without rules, invoking the

“serious play” of children, who need no instructions to use a sandbox

but simply start digging. The reader initiates his or her own process of

creative synthesis, choosing to manipulate, arrange, define, or ignore

the words printed on each side of the cards.

|

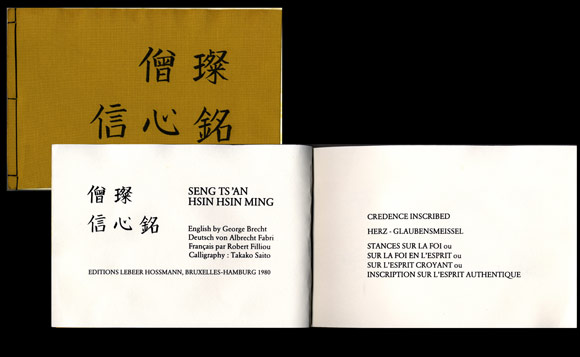

Seng Ts’an. Hsin hsin ming. Calligraphy by Takako Saito, translated by George Brecht, Albrecht Fabri, and Robert Filliou (Lebeer Hossmann, 1980).

The collaborative nature of Fluxus and

its members’ shared interest in Zen Buddhism found a linguistic outlet

in this polyglot translation of Seng Ts’an’s seventh-century writings on

Chinese Buddhism, for which Saito provided the calligraphy in k’ai shu style.

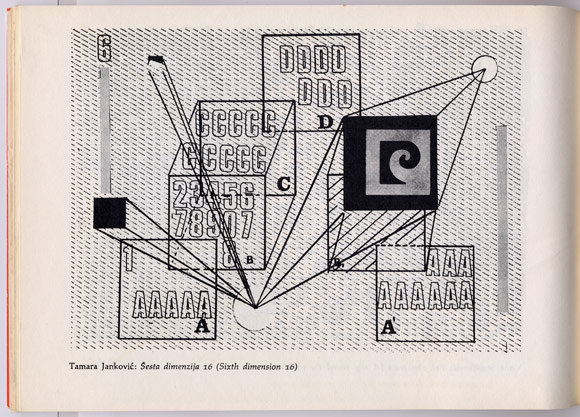

Tamara Janković. Šesta Dimenzija 16 and Šesta Dimenzija 17. In Signal, no. 1 (1970).

Janković was a member of the

Belgrade-based Signalist group of experimental poets in the early 1970s

and was on the editorial board for the group’s magazine, Signal.

Her use, here, of numbers, letters, and the Pierre Cardin logo reflects

the Signalist goal to explore symbols and imagery in new poetry that

transcends national languages.

Carolee Schneemann. Meat Joy Notes as Prologue. In Some/thing 1, no. 2 (1965).

Schneemann created a new, bilingual work from her notes to her stage performance Meat Joy with this playful technique: “The French text was made from a dictionary and a picture book, Look and Learn, then collaged and superimposed on the English, along with the sound of a ticking clock.”

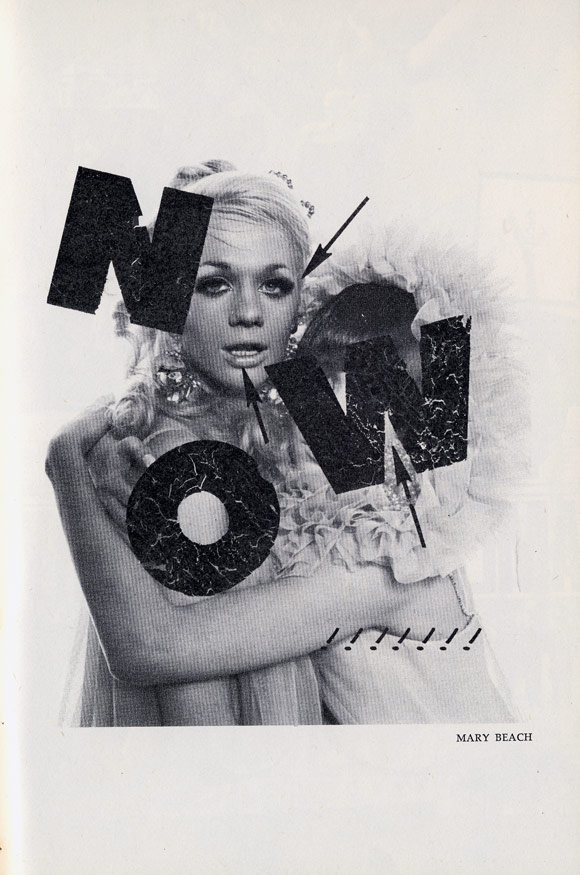

Mary Beach. Concrete poem. In The San Francisco Earthquake 1, no. 3 (1968).

Beach’s calligraphs, Concrete poems, and

experimental prose circulated along with works by Carol Bergé, Diane di

Prima, and Diane Wakoski in the network of publications in which

Fluxus, Beat poetry, and other underground writing converged.

|

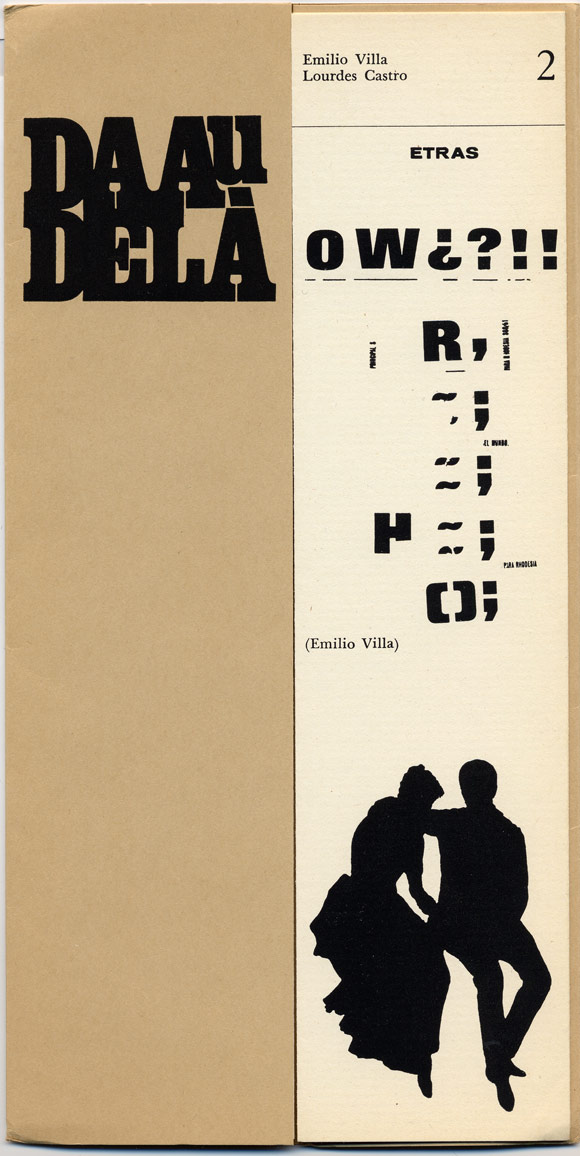

Lourdes Castro and Emilio Villa. Visual Poem (Untitled)In Da-a/u dela, no. 1 (1966).

To this collaboration with Villa,

an Italian experimental poet, Castro contributed male and female

silhouettes whose ambiguous embrace invites the reader to interpret

Villa’s symbols above. Castro was a coeditor of the artists’ magazine KWY, which published poetic and visual works by Fluxus artists.

Yvonne Rainer. Three Distributions. In Aspen, no. 8 (1970-71).

Rainer, a dancer and filmmaker,

transcribed movement using text, graphic diagrams, and images of bodies

in her contribution to the Fluxus issue of Aspen.

|

Mediating the Body

Fluxus performers staged their bodies in

social, interactive spaces, drawing attention to everyday tasks,

movements, and objects. Women artists who made explicit and erotic uses

of their bodies in their work sometimes sensed disapproval from the

group. Shigeko Kubota recalls that her fellow Fluxus artists were

visibly displeased by the graphic nature of Vagina Painting (1965),

while Carolee Schneemann became alienated from Fluxus organizer George

Maciunas following the productions of her sensual stage show Meat Joy

(1964). Fluxus women and those on the periphery of the movement

continued to investigate the body in different mediums, exploiting the

immediacy of performance and the more distanced confrontations enabled

by visual art, the book arts, and video. These exhibition catalogues and

artists’ books document some of these uses of the naked female form.

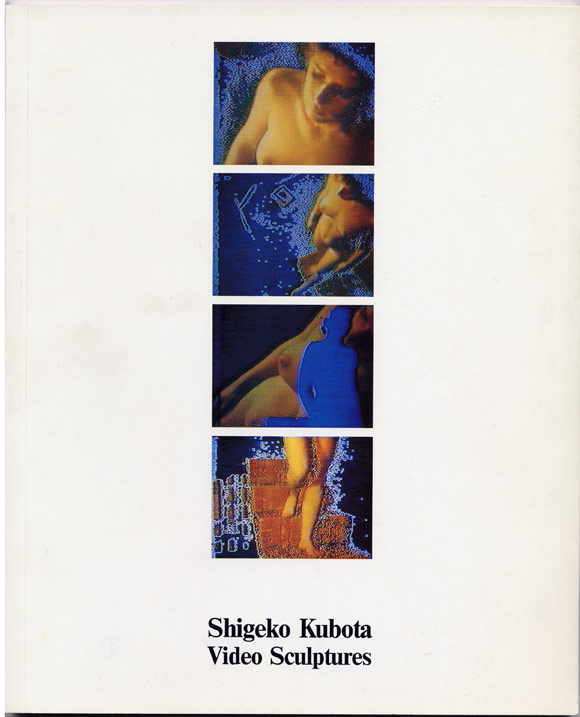

Shigeko Kubota. Nude Descending a Staircase. 1975–76. In Shigeko Kubota: Video Sculptures, ed. Zdenek Felix (Museum Folkwang Essen, 1981).

Following her early Fluxus performances

and objects, Kubota began the pioneering career in video art and

installation in which she continues to investigate the landscapes of the

body and the natural world. In this homage to her mentor Marcel

Duchamp, Kubota deconstructs the moving body of filmmaker Sheila

McClaughlin to produce a new iteration of Duchamp’s painting of the same

title.

Carolee Schneemann. Meat Joy (1964) and Fluxus (1990). In Ubi Fluxus Ibi Motus: 1990–1962, ed. Achille Bonito Oliva (Mazzotta, 1990).

Fluxus can be lots of fun when the boys let you on their boat / sometimes they throw you off the boat. / . . .

/ if you dont wear underpants or show your pussy you get pushed / over the side.

/ if you dont wear underpants or show your pussy you get pushed / over the side.

Schneemann’s

explorations of eros in her maverick stage performances pioneered the

American genre called body art. In this catalogue for a 1990 Fluxus

exhibition, Schneemann paired sensuous imagery from Meat Joy with a retrospective statement about the group.

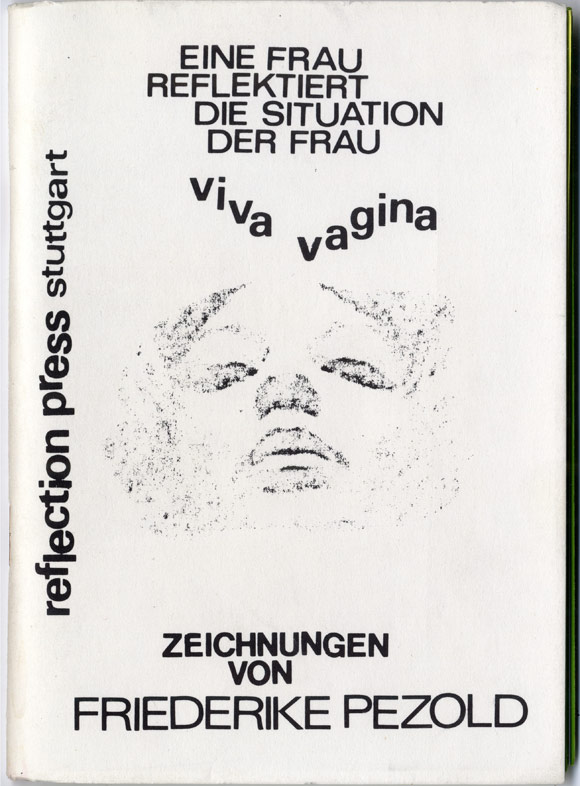

Friederike Pezold. Die Schwarz-Weisse Göttin und ihre Neue Leibhaftige Zeichensprache (Staatliche Kunsthalle, 1977).

Pezold’s early artists’ books,

published by Reflection Press (run by Fluxus participant Albrecht d.),

address issues of women in art in the early 1970s. In later performance,

film, writings, and visual art Pezold reduced the female body to

abstract hieroglyphics and often recomposed these elements in

photographic installations and video sculptures.

|

|

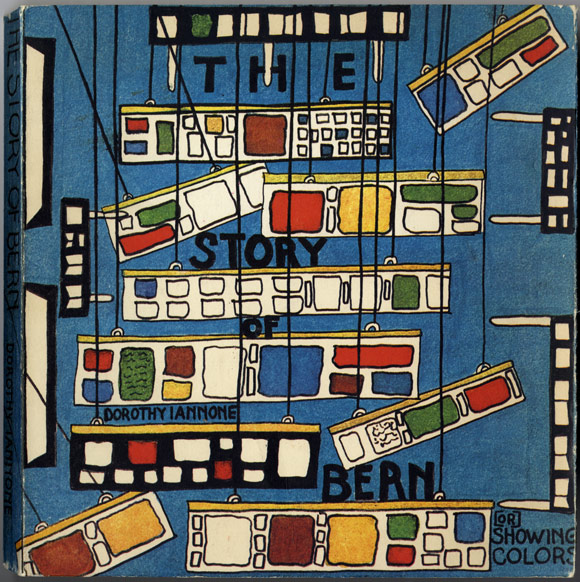

Dorothy Iannone. The Story of Bern, or Showing Colors (Dieter Roth and D. Iannone, 1970).

Iannone takes as her subject the

interrelations of love, sex, and spirituality. Although she is not

viewed as a full member of the group, Iannone contributed to Fluxus

publications and formed part of a social circle that included artists

Emmett Williams and Dieter Roth. At a 1969 exhibition in Bern, her

explicit imagery of male and female genitalia was censored. Roth

withdrew his works from the show in protest and the gallery’s director,

Harald Szeemann, resigned. Iannone processed the experience in this

artist’s book, which illustrates the scandal in detail.

Helen Chadwick. Of Mutability (London Institute of Contemporary Arts, 1986). Library copy

Chadwick was part of the vibrant Fluxus

community in England in the early 1970s. In these blue photocopied

collages Chadwick refers to Edmund Spenser’s Renaissance verses on the

forces of flux and entropy inherent to the universe, depicting her own

body within an amniotic environment of decaying organic matter.

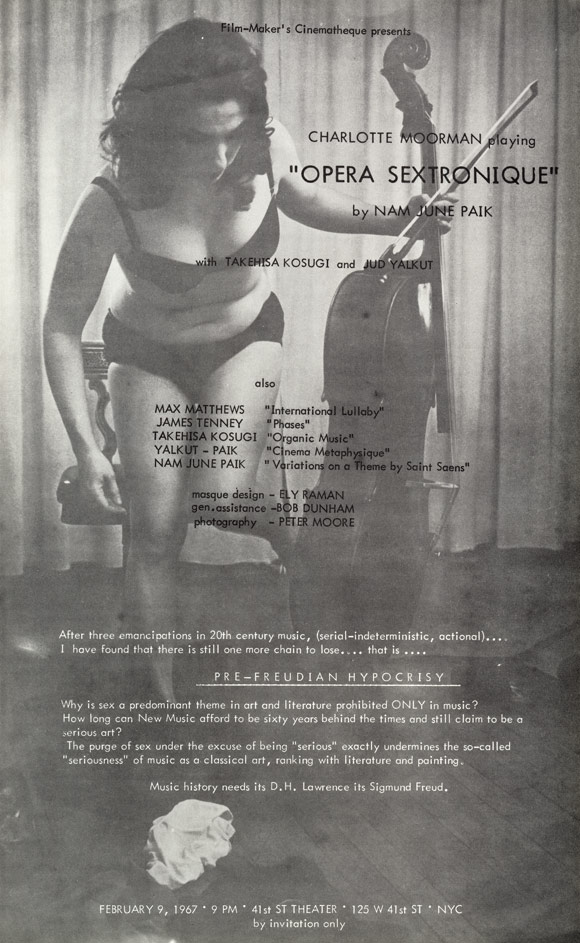

Charlotte Moorman. Flyer for Opera Sextronique. In The World of Charlotte Moorman Archive Catalog, ed. Barbara Moore (Bound & Unbound, 2000). Library copy

Moorman used her

body as a “living sculpture,” often performing in various states of

undress and costume. After removing her bikini top at a 1967 performance

of Opera Sextronique in New York—one of her many

collaborations with Nam June Paik—she was arrested, charged, and given a

suspended sentence for lewdness, becoming known in the media as “the

topless cellist.”

Kate Millet. Sexual Politics (Doubleday, 1970).

Fluxus artist Kate Millet combined

cultural and literary criticism in a work that became an important text

for the developing fields of women’s studies and feminist theory.

Book-making

| The emergence of artists’ books toward the end of the 1960s is inextricably linked to Fluxus and the Museum Library. Members of the group contributed to the early production of printed matter, which helped to set the stage for later developments in the genre. The women artists featured here created—and continue to create—conceptual, poetic, and narrative works, books as sculptural installations and as objects, and are also printers, publishers, editors, book dealers, and archivists. When the Silverman Reference Library was acquired, copies of some of its works were already in different sections of the Library—many in the |  |

| Franklin Furnace Artists’ Books Collection—revealing intersections among collecting practices that speak to the influence of Fluxus on the contemporary book arts and the institutions dedicated to preserving the book as a work of art. | |

Alison Knowles. The Big Book. In Décollage, no. 6 (1967).

Knowles’s walk-through installation The Big Book

included objects and images of daily living—a saucepan, a telephone, a

toilet—within a three-dimensional framework of eight-foot “pages.”

Knowles’s work is performative in function, inviting bodies to

experience the space in time, through their own, indeterminate

“readings.”

Peter Moore. The Big Book, by Alison Knowles. c. 1967. Franklin Furnace Artist Files. © Estate of Peter Moore / VAGA, New York

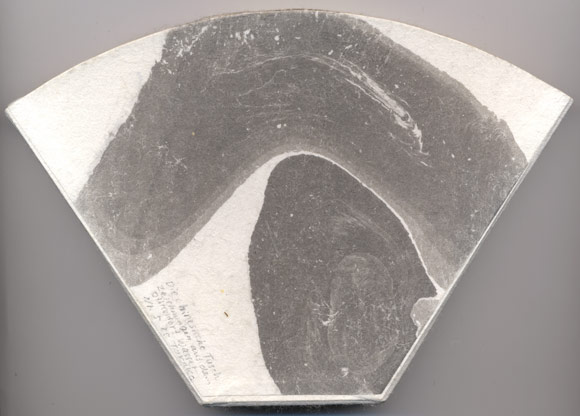

Takako Saito. Die Chinesisch Tusch Zeichnungen auf dem Düsseldorf Wasser (Noodle Edition, 1985).

A prolific artist of sculptural book

forms and book objects, Saito suggests the melancholy of self-exile

through the daily detritus of used coffee filters, connecting her Asian

origins to the country in which she lives by combining Chinese ink with

German water.

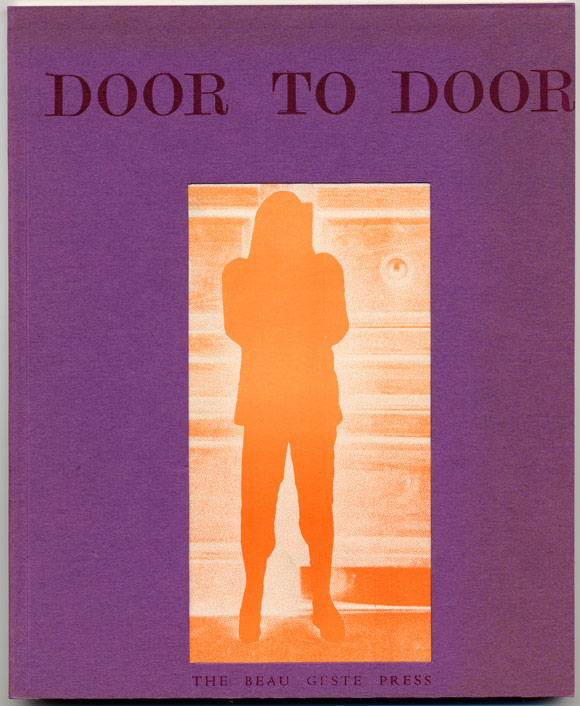

Helen Chadwick and David Mayor. Door to Door (Beau Geste Press, 1973).

In Croydon, two doors face each other across a lawn.

The contesting pagination in Chadwick

and Mayor’s conceptual photobook draws the reader simultaneously

backward and forward through the book. Chadwick’s figure, captured from

near and far, parallels this spatial disorientation by seeming to

magically move from one distant doorway to another.

Barbara Moore. Cookpot (ReFlux Editions, 1985). Reproduction of cover image supplied by B. Moore, 2010.

Individual personalities and practices

inflect each contributor’s notion of what constitutes cooking in Moore’s

collection of recipes by friends and fellow artists. Carolee

Schneemann, for example, prescribes multiple roles for one cantaloupe:

dried beads for children, food for cats, material for a facial, and,

finally,

a high-protein breakfast.

a high-protein breakfast.

|

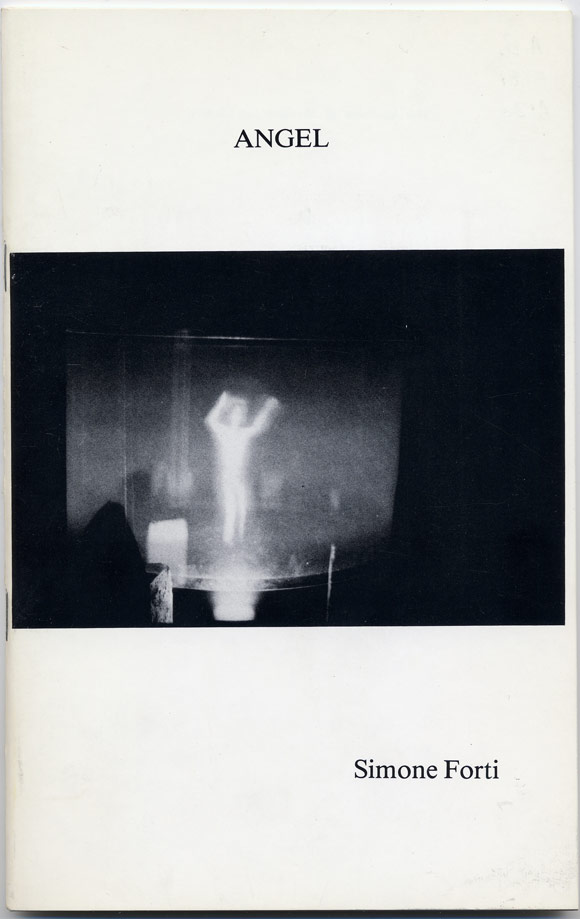

Simone Forti. Angel (Self-published, 1978). Franklin Furnace Artists’ Books Collection

Forti’s book of short prose poems and photographs

produces a nonlinear narrative of thought and memory that reflects the

artist’s changing engagement with her work and life.

Lourdes Castro. D’Ombres (G. Schraenen, 1974). Franklin Furnace Artists’ Books Collection

Using a combination of colored sheets, vellum, and transparent covers, Castro used photographs from her Théâtre d’Ombres

project as the basis for this screenprinted artist’s book. Her

silhouetted figure, almost indistinguishable from the shadowy objects

around her, suggests both presence and absence.

As she moves through the book, Castro’s form “comes to life” even as it appears to dematerialize in front of the reader’s eyes. |

Citations (from top) and Additional Texts

Charlotte Moorman at 24 Stunden, a Happening at Galerie Parnass, Wuppertal, 1965. In 24 Stunden (Hansen & Hansen, 1965). Photograph by Ute Klophaus

24 Stunden. Hansen & Hansen, 1965

Happenings, Fluxus, Pop art, Nouveau Réalisme: eine Dokumentation, ed. Jürgen Becker and Wolf Vostell (Rowohlt, 1965)

Store Days: Documents from The Store, 1961, and Ray Gun Theater, 1962, ed. Claes Oldenburg and Emmett Williams (Something Else Press, 1967)

Shigeko Kubota. Vagina Painting. 1965. In VTRE, no. 7 (1966). Photographs by George Maciunas

Yoko Ono: En Trance, tilrettelagt af Jon Hendricks og Birgit Hessellund (Randers Kunstmuseum, 1990)

Happenings, Fluxus, Pop art, Nouveau Réalisme: eine Dokumentation, ed. Jürgen Becker and Wolf Vostell (Rowohlt, 1965)

Store Days: Documents from The Store, 1961, and Ray Gun Theater, 1962, ed. Claes Oldenburg and Emmett Williams (Something Else Press, 1967)

Shigeko Kubota. Vagina Painting. 1965. In VTRE, no. 7 (1966). Photographs by George Maciunas

Yoko Ono: En Trance, tilrettelagt af Jon Hendricks og Birgit Hessellund (Randers Kunstmuseum, 1990)

An Anthology, 2nd ed., ed. La Monte Young (H. Friedrich, 1970)

Alison Knowles. Journal of the Identical Lunch (Nova Broadcast Press, 1971)

Womens Work, ed. Anna Lockwood and Alison Knowles (Self-published, 1975)

Mieko Shiomi. Spatial Poem (Self-published, 1976)

Esther Ferrer: Ekintzatik Objektura, Objektutik Ekintzara. Gipuzkoako Foru Aldundia, 1997. Promotional postcard

Alison Knowles. Journal of the Identical Lunch (Nova Broadcast Press, 1971)

Womens Work, ed. Anna Lockwood and Alison Knowles (Self-published, 1975)

Mieko Shiomi. Spatial Poem (Self-published, 1976)

Esther Ferrer: Ekintzatik Objektura, Objektutik Ekintzara. Gipuzkoako Foru Aldundia, 1997. Promotional postcard

Mieko Shiomi. As It Were Floating Granules (Japan Federation of Composers, 1976)

Marian Zazeela. Lines. In Selected Writings, Copyright © La Monte Young and Marian Zazeela 1969 (Heiner Friedrich, 1969, Munich)

Karlheinz Stockhausen. Stimmung, für 6 Vokalisten, nr. 24 (Universal Edition, 1969)

Bici Hendricks. Language Box, Box Language (Black Thumb Press, 1966)

Seng Ts’an. Hsin hsin ming. Calligraphy by Takako Saito, translated by George Brecht, Albrecht Fabri, and Robert Filliou (Lebeer Hossmann, 1980)

Tamara Janković. Šesta Dimenzija 16. In Signal, no. 1 (1970)

Mary Beach. Concrete poem. In The San Francisco Earthquake 1, no. 3 (1968)

Lourdes Castro and Emilio Villa. Visual Poem (Untitled). In Da-a/u dela, no. 1 (1966)

Marian Zazeela. Lines. In Selected Writings, Copyright © La Monte Young and Marian Zazeela 1969 (Heiner Friedrich, 1969, Munich)

Karlheinz Stockhausen. Stimmung, für 6 Vokalisten, nr. 24 (Universal Edition, 1969)

Bici Hendricks. Language Box, Box Language (Black Thumb Press, 1966)

Seng Ts’an. Hsin hsin ming. Calligraphy by Takako Saito, translated by George Brecht, Albrecht Fabri, and Robert Filliou (Lebeer Hossmann, 1980)

Tamara Janković. Šesta Dimenzija 16. In Signal, no. 1 (1970)

Mary Beach. Concrete poem. In The San Francisco Earthquake 1, no. 3 (1968)

Lourdes Castro and Emilio Villa. Visual Poem (Untitled). In Da-a/u dela, no. 1 (1966)

Shigeko Kubota: Video Sculptures, ed. Zdenek Felix (Museum Folkwang Essen, 1981)

Friederike Pezold. Eine Frau Reflektiert die Situation der Frau : Viva Vagina (Reflection Press, 1973)

Dorothy Iannone. The Story of Bern, or Showing Colors (Dieter Roth and D. Iannone, 1970)

Flyer for Opera Sextronique. In The World of Charlotte Moorman Archive Catalog, ed. Barbara Moore (Bound & Unbound, 2000).

Friederike Pezold. Eine Frau Reflektiert die Situation der Frau : Viva Vagina (Reflection Press, 1973)

Dorothy Iannone. The Story of Bern, or Showing Colors (Dieter Roth and D. Iannone, 1970)

Flyer for Opera Sextronique. In The World of Charlotte Moorman Archive Catalog, ed. Barbara Moore (Bound & Unbound, 2000).

Yoko Ono. Grapefruit: a Book of Instructions. Simon and Schuster, 1970

Takako Saito. Die Chinesisch Tusch Zeichnungen auf dem Düsseldorf Wasser (Noodle Edition, 1985)

Helen Chadwick and David Mayor. Door to Door (Beau Geste Press, 1973)

Simone Forti. Angel (Self-published, 1978)

Takako Saito. Die Chinesisch Tusch Zeichnungen auf dem Düsseldorf Wasser (Noodle Edition, 1985)

Helen Chadwick and David Mayor. Door to Door (Beau Geste Press, 1973)

Simone Forti. Angel (Self-published, 1978)

Further Reading

Fluxus, etc.: the Gilbert and Lila Silverman Collection, ed. Jon Hendricks. Bloomfield Hills, Mich.: Cranbrook Academy of Art Museum, 1981.

Hannah Higgins. Fluxus experience. Berkeley: University of California Press, c2002.

Ubi Fluxus Ibi Motus, 1990-1962, ed. Achille Bonita Oliva. Milano: Mazzotta, 1990.

Women & Fluxus: Toward a feminist archive of Fluxus, ed. Midori Yoshimoto. Special issue of Women & Performance: a journal of feminist theory, vol. 19, no. 3 (2009).

Midori Yoshimoto. Into Performance: Japanese Women Artists in New York. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers Univ. Press, 2005.

All material in this exhibition is held by The Museum of Modern Art Library. Contact library@moma.org for an appointment.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Jon Hendricks, Barbara Moore, Mieko Shiomi, Ute Klophaus and Armin Hundertmark.Also thanks to Rebecca Roberts, Sara Bodinson, David Hart, Julianna Goodman, Chiara Bernasconi, Jessica Nutting, Roberto Rivera, Robert Kastler, Thomas Griesel, Charlie Kalinowski, Milan Hughston and the entire MoMA Library staff.

(((SOURCELINK)))

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDelete

ReplyDeleteGreat information here. Thank you for sharing. If you are ever in a need of

locksmith denver Services we are Aurora Locksmith Services. You can find us at auroralocksmithco.com.com or call us at: (720) 220-4851.

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDelete